Today marks the last article on neuronal communication. In the past two articles, we saw how neurons are able to transmit information with each other. Today, we will see how this information is used, mostly through the understanding of neuromuscular junction.

To understand how neuron use the information, we first need to understand where it is originally from. Simply put, neuronal information is a response to a stimulus. For example, if you are touched, sensory neurons on the skin will transform the touch into electrical information. This information will go to many places: first in the brain, to inform it that touch is happening, but then to other neurons in the perimeters to tell them that the touch is not painful and they should not activate. However, one of the main response to a stimulus is movement. Indeed, if for instance you were to touch something hot, the neurons will tell your hand to move it away from it. Neurons also tell you everyday to walk, use your lung muscles to breathe, etc… And most if not all movement starts at the neuromuscular junction [source].

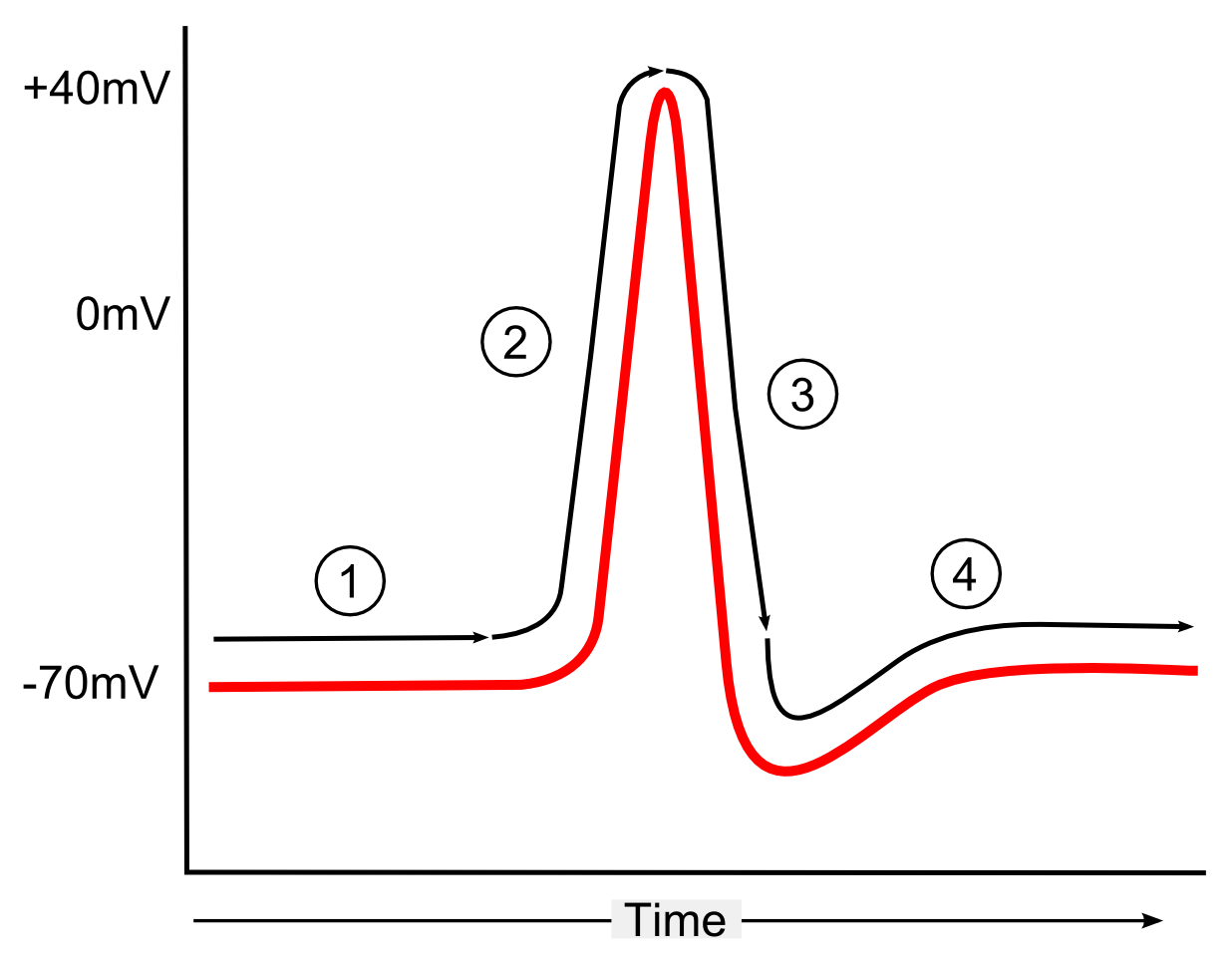

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is a specialized synapse, but instead of a pre- and postsynaptic neuron, we have a presynaptic neuron and a muscle. In this scenario, the presynaptic neuron receives an action potential, which will travel down the neuron towards the NMJ. There, it will activate the release of neurotransmitters. In this case, the main neurotransmitter is acetylcholine (Ach). These neurotransmitters will bind to the receptors nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAchR) at the muscle membrane. When Ach binds, it causes an influx of ions, similar to any synapse. However, instead of creating an action potential, this influx of ion will cause muscle contraction, and initiate movement [source].

The example of NMJ can also show us the importance of neurotransmitters. Depending on which one is used, the information will be treated differently. Similarly, a neurotransmitter may have different receptors, and depending on which one is activated, the answer will be different. An example for this will be from specific neurons in the brain called medium spiny neurons (MSNs). These neurons are the customs of movement, they either allow or forbid it. Such drastic difference in response is explained by a difference in receptors. While all MSNs receive the neurotransmitter dopamine, some MSNs will express the dopamine D1 receptor, which will activate the movement, while the others express the dopamine D2 receptor, which will prevent it [source].

Overall, neuronal communication is a complex concept that mixes both electricity and chemistry. But while the mechanism is nearly always the same, the results can be drastically changed thanks to slight modification such as neurotransmitter use.